The ALSTDI is constantly testing potential ALS research and treatments and pushing them through their pipeline like time is of the essence. And it is.

In Watertown, MA, the ALS Therapy Development Institute (ALSTDI), the worlds first and largest nonprofit biotech, operates the most comprehensive drug discovery lab focused solely on ALS.Funded entirely by donations, ALSTDI was the first nonprofit biotech in any disease state to attempt to move a drug invented in its own lab and into clinical trials” (ALSTDI).

Scientists at ALSTDI invented AT-1501, a homegrown molecule that is currently in clinical testing as a potential drug treatment for ALS.

AT-1501 could be a game-changer.

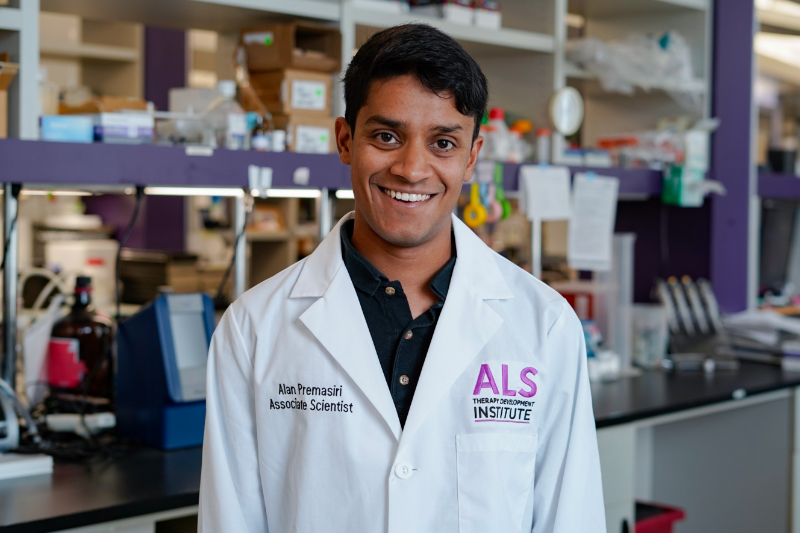

We recently had the pleasure of sitting down with Alan Premasiri, Manager of Clinical Operations and Associate Scientist for the Watertown research lab, to learn more about their work and how ALS patients can team up with their scientists to further clinical research towards a cure.

What makes ALSTDI stand out amongst other biotechs and ALS organizations?

ALSTDI is unilaterally focused on one thing: finding or inventing treatments for ALS.

When James Allen Heywood’s brother Stephen was diagnosed with ALS at the age of 29, he launched a preclinical lab in his home basement with the goal of conducting therapeutic research, an area of study that hadn’t yet been addressed in 1999. Though Stephen passed away, the homegrown operation has grown into one of the foremost ALS drug discovery labs on the planet, and has made invaluable contributions to ALS research, including the discovery and development of a potential treatment, AT-1501, which the ALSTDI has pushed through their labs, FDA review, and now into clinical trial.

(Learn more about AT-1501 here.)

Alan Premasiri offered a look at how this basement operation grew into a leading research institute.

“Most of the history of the TDI is drug discovery,” Premasiri says. The nonprofit research organization initially included two branches that focused on drug discovery and discovery biology, respectively, but in 2013 it added a Clinical Team of Precision Medicine Program and a Translational Science Team. He describes Translational Research as “using research models that are closer to human biology so that potential treatments can be more quickly moved into trials.”

Premasiri is part of the Precision Medicine Program, and splits his time between managing clinical operations and the “nitty gritty, academia work” of a bench scientist. Think: looking at cells through a microscope and writing papers. His research focuses on the C9orf72 mutation, which is the most common genetic mutation that causes familial ALS.

“C9orf72 is a gene that we all have,” Premasiri explains. “In people with ALS, there’s a section of that gene that just repeats and expands way beyond it’s normal length.”

In 2020, Premasiri, fellow scientist Anna Gill, and CEO/CSO Fernando Vieira published an article detailing their study that “reveals a novel mechanism that can contribute to arginine-rich DRP toxicity and suggests a possible therapeutic strategy through Type I PRMT inhibition.” In other words, a potential treatment. A lead. A hope. A big step in the right direction.

Premasiri talked us through the Precision Medicine Program in more detail.

“It’s a Clinical Observational Study, so there’s no drug being tested,” he explained. “It’s all about monitoring progression and learning from that. ” While clinical monitoring was certainly prevalent in other disease indications, this strategy was difficult in ALS research for several reasons. First, the rapid progressive nature of the disease makes it hard to monitor ALS patients long term when the average patient’s life expectancy is three to five years. Second, Premasiri says, “studies can be limited to location of the research site,” and patients often experience difficulty traveling as the disease progresses. With the Precision Medicine Program, he adds, “the research is all done remotely. We can enroll people from almost anywhere, and the burden of travel doesn’t become an issue for folks. Ultimately, we capture a lot of data this way.”

But despite these challenges, the observational work is critical.

Observational research, says Premasiri, is in part about trying to get ahead of the disease. “Can we understand ALS better by measuring progression, not having to do that after looking at their tissue samples after [patients] have passed? Can we develop some method to track ALS better? Or maybe even predict somebody’s progression, notice it quicker? Anything like that.”

Anything to make a difference.

The Precision Medicine Program leverages five points of data collection to drive their observational research. The goal of the program is to collect as much comprehensive data as possible. As Premasiri explains for clinical trials in ALS, “If you want to get a good data set, you need to enroll a lot of people, because the data gets very noisy. ALS itself is already so heterogeneous in its presentation, it’s just rife for variability.”

1. Questionnaires

One of the first steps in clinical observation is completing the ALSFRS (The Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis Functional Rating Scale), which is a widely-used 12-question questionnaire asking patients to rate their ability to complete daily tasks on an integer scale of zero to four. “It’s trusted enough that the field usesit as the primary outcome measure for a clinical trial,” Premasiri explains. “But there are limitations to it. It’s subjective, how do you rate if I’m good at this or great at this, or bad?” One of the Precision Medicine Program’s largest aims, he says, is to find a supplementary measurement tool that can be used alongside the ALSFRS questionnaire and help some of the ambiguous subjectivity.

2. Surveys

“We capture surveys of a wide variety. Medical history, family history, occupation — anything that might give us a little bit more insight into people’s past and their environment and how they grew up.”

3. Voice Recordings

“Once a month people call in and read a set of five phrases on the phone.” To measure speech dysarthria (or speech loss), ALSTDI uses a machine learning model developed specifically for them in collaboration with the minds at Google.

4. Accelerometers

“We send these wearable accelerometers. We send four for them to wear on their ankles and wrists. And we have them do a set of exercises three times a week, one week out of each month. They do seated arm lifts, leg lifts, and they bend over and touch their toes so we can measure their limb strength objectively”.

5. In-Home Blood Collection

In 2019, ALSTDI began working with a phlebotomy network to send a phlebotomist out to patients’ homes for blood samples. “The goal of that is to hopefully find something that’s been very elusive in ALS — a blood-based biomarker indicator of ALS…something like blood glucose levels for diabetes.”

As Manager of Clinical Operations and an Associate Scientist, Premasiri has a foot in both ends of the ALS research pool. There’s the quantitative data collection and analysis, and the personal interactions of observation. It’s the interpersonal side of ALS research that has grown his work into something greater than a career.

“You definitely feel like you’re racing against the clock,” he shared. “Especially when a lot of people here have connections to somebody with ALS. A lot of us have had that thought, ‘Damn! I wasn’t in time.’ But, broadly speaking for science, a failed experiment can be good information. ‘Something didn’t work’ is useful knowledge. So even if we say something’s a failure, in a sense it doesn’t always feel that much like a failure. In the sense of time it feels like it. But in the sense of knowledge, you learned something.”

Premasiri perfectly summed up so much of the fight against ALS. The faith, the investment…the knowledge that our efforts today will not likely pay off in this lifetime, but if we work relentlessly towards discovering a cure, we may be able to save lives in future generations.

The clinical role allows him to talk to people with ALS every day, and puts names and faces to the work he conducts in the lab. Those patients are his drive, his why. “Every conversation I have is just…it’s different now. Everything I’m doing is for them.”

How to get involved with ALSTDI research.

While the team at ALSTDI pours countless hours into research and development, and its donors and partners give generously, Premasiri says, “the success of our program is as much us executing it as it is people being willing to give their time to it.” A cornerstone of ALSTDI’s research success and contributions to the fight against ALS is patient participation. “We’re not offering a treatment in this program. So, it really is a lot of people offering data to help advance ALS research .”

“We’re open to anybody anywhere, pretty much on the planet,” Premasiri says. “You don’t have to speak English; you just have to understand and write it. You can participate from anywhere.” As a nonprofit, ALSTDI ensures that there is never any cost to the patients who participate in their studies.

Getting started is as easy as enrolling on their website.

“Some people only participate maybe once every other month and do one thing every other month. We’ll appreciate whatever you can give us. We want it to be easy. We don’t add troubles to their lives.”

ALSTDI also offers ALS advocates non-clinical ways to contribute to research endeavors. Their lab is funded entirely by the generosity of the ALS community, and lives by the dogged belief that “ALS is not incurable, it is underfunded.” From grass-roots fundraising events to corporate opportunities, their team provides for everyone who envisions a cure for ALS to get involved.

About SimpliHere

The mission of SimpliHere is to ensure efficient care and peace of mind for caregivers and their patients with neurological conditions that impact communication and mobility. Joanna Rosenberg founded SimpliHere to address communication gaps between caregivers and patients. Her personal experience when her mother lived with ALS exposed the challenges of communicating and understanding basic needs, as well as managing daily tasks. Download SimpliHere today!

Emma Comery is a freelance Writer & Content Contributor with a passion for using language to spotlight incredible humans and movements. She is currently pursuing her MFA in Creative Nonfiction at Old Dominion University.